In this week’s field report, George talks about specific birds as well as the overall report of his 2018 Black Guillemot census on Cooper Island.

Nature, when observed or monitored for any extended period, typically provides a predictability that is reassuring in its consistency and sufficient surprises to keep one engaged.

For over four decades, my first task after I set up camp was a census of the Cooper Island Black Guillemot colony. This year was an excellent example of this balance of the expected and unexpected.

Since the 1970s, the majority of the birds breeding in the colony have had, in addition to a numbered metal band, a unique combination of color bands allowing identification with binoculars of individual birds. My census of the colony consists of recording the number of occupied nest sites and the color band combinations of the individuals occupying each site. This allows me to determine the birds who survived the winter since last year’s breeding season and whether they have retained the same nest site and mate.

Black Guillemots, like most seabirds, have high annual survival of adult birds and high mate and nest-site fidelity. On average 90 percent of the individuals breeding on Cooper have returned the following year with mate and nest-site fidelity over 95 percent. With loss of breeding birds so uncommon and changes in mate and nest site so rare, past censuses consisted primarily of confirming last year’s pair was again occupying a particular nest site. For the small number of nests where one member of a pair did not return, there typically was a new recruit already occupying the vacancy by the time of my census–either a bird banded as a nestling on Cooper Island or an immigrant, indicated by its lack of any bands.

In the past, the high survivorship of breeding birds meant that some of the individuals I resighted each June were ones I had seen for over 20 years, and in many cases had known since I had weighed them daily as a nestling. The resightings of these individuals as adults provided an annual touchstone that was an important part of both my emotional and scientific connection to the colony.

My initial census of the colony this year was unlike any in the past. The loss of breeding birds over the winter was the highest on record. Nearly one-third of the 170 birds that bred in 2017 not returning to the colony in 2018.

As mentioned in an earlier post, many of the 50 pairs that had eggs this year (down from 85 in 2017 and 100 in 2016) consisted of widowed birds that both lost a mate over the winter. The decrease in breeding population was exacerbated by the paucity of previously nonbreeding birds present to recruit into the breeding population. Some established breeders widowed over the winter are the sole occupants of their nest sites. Even pairs that did survive the winter have shown much lower mate and site fidelity than I have observed in previous years.

The disturbingly high percentage of birds lost to overwinter mortality comes as a major surprise but a simple percentage fails to capture the full impact of what I experienced during this year’s census.

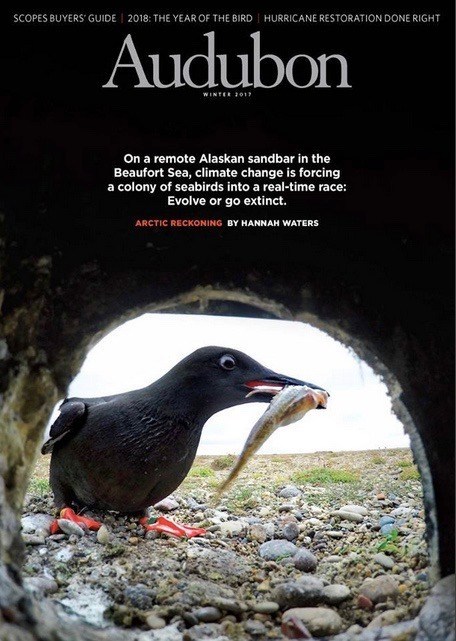

Many of the individual birds I have known for decades were among those absent from the colony. Most notable was Yellow-Gray- Green, a 21-year-old female banded as a chick in 1996 and breeding on Cooper since 2001. She was featured on the cover of last winter’s Audubon magazine. Another individual absent this year with an even longer history on the island is White-Gray-Blue, who fledged from Cooper in 1989 and bred on the island during 23 years of rapid environmental change including of decreases in sea ice, warming ocean temperatures, increased polar bear nest predation and major shifts in prey availability.

While examining this year’s colony census at the level of the individual bird, versus a review of declining numbers is disheartening, it also provides some reasons for optimism–a rare feeling this field season.

My census found that a number of birds fledged from Cooper in recent years recruited into the breeding population this year, starting what I hope will be a long and productive career as breeders. These birds, and their young–the fledging chicks we hope they produce later this summer–provides one both with optimism and motivation to maintain the long-term study. As Hannah Waters pointed out in her excellent article in Audubon magazine, the guillemots are going to have to adapt and evolve for the colony to survive in a rapidly warming Arctic.

The hope that this year’s first-time breeders and their young will find a way to maintain the colony during the major changes occurring in the Arctic allows me to maintain a positive attitude as I continue to monitor this year’s breeding season.