For 13 years NOAA has released an annual “Arctic Report Card“. That NOAA feels the need to issue a report on the an annual basis reflects the rapid pace of change occurring in the region. As in past years the 2018 Arctic Report Card was released at the Annual Meeting of the American Geophysical Union (AGU), this year occurring on 9-14 December in Washington D.C.

The reports provide a concise annual summary of major physical and biological changes documented in the Arctic over the past year and also serve to focus the media and public on the larger issue of global warming. We attended the meeting to report on our 2018 findings (see below) and our recent and long-term observations from the Cooper Island Black Guillemot colony were of interest to a number of journalists as examples of a biological response to the melting Arctic. The Associated Press mentioned our observations in their story about the report card and Inside Science has a good piece with the details of the depressing 2018 field field season.

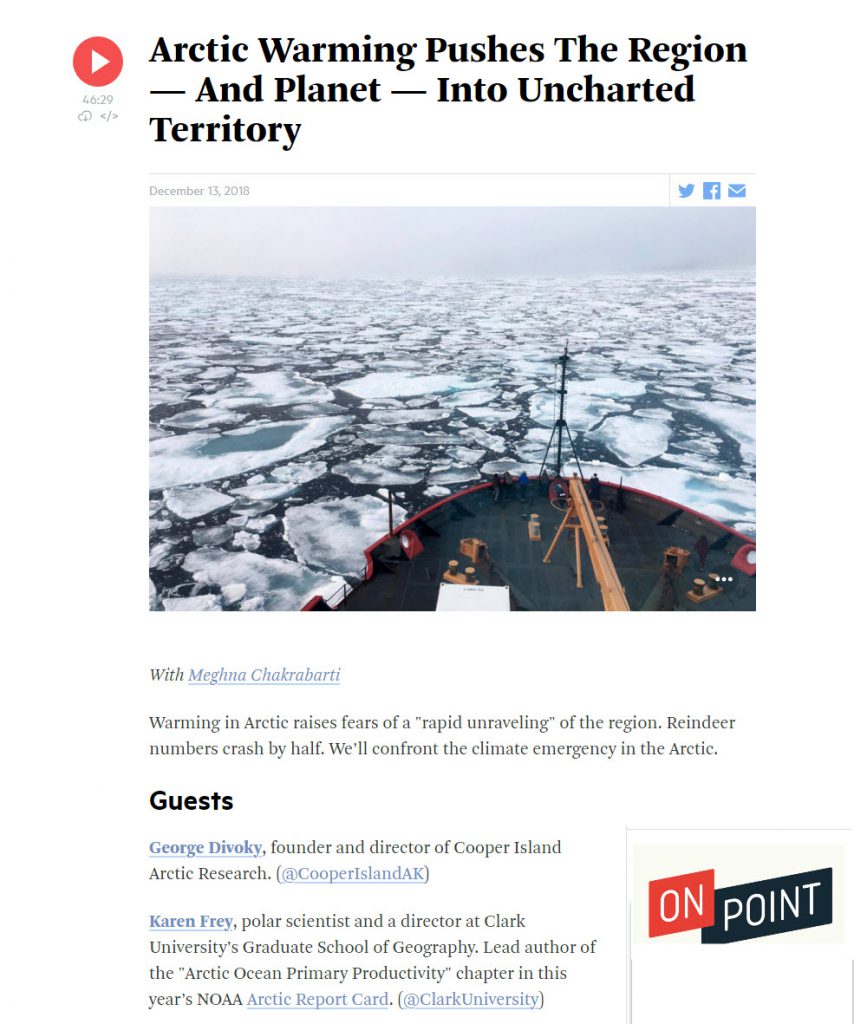

Due to the release of the Report Card and thanks to a recent article in Politico by Eric Scigliano on his trip with me to Utqiagvik, I was asked to be on the national NPR radio show “On Point” to discuss the “rapid unraveling of the Arctic”. Karen Frey, a sea ice expert from Clark University and one of the authors of this year’s Arctic Report Card, joined me to be interviewed by Meghna Chakrabarti. The interview, including calls from listeners, can be accessed by clicking on the image below.

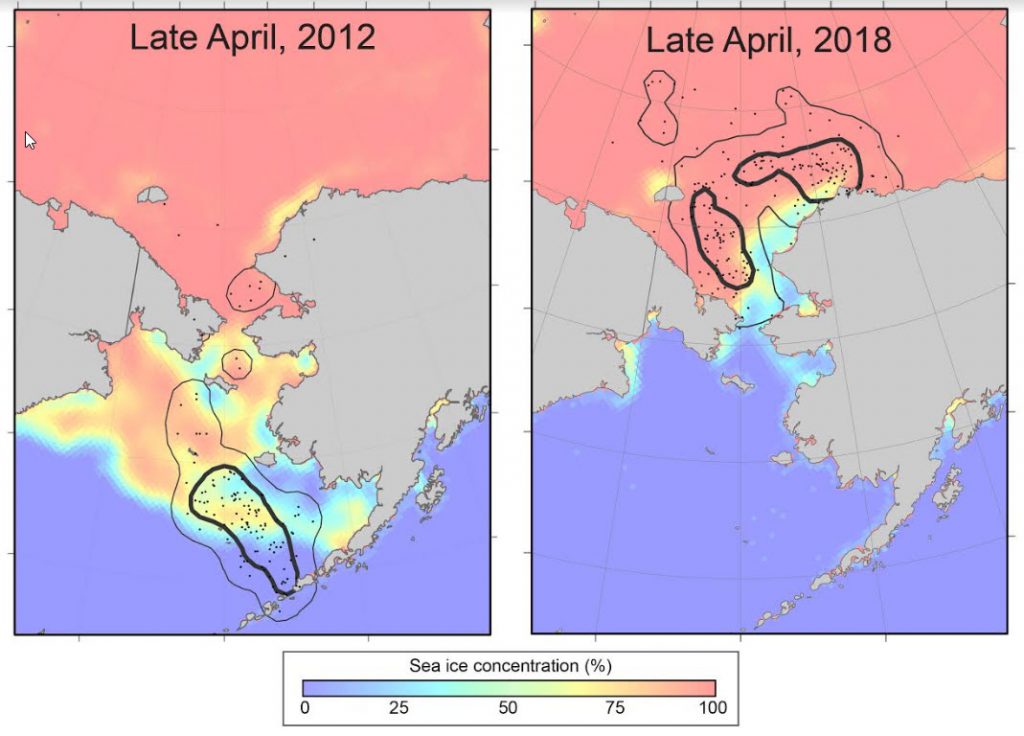

Last winter’s historically low ice extent in the Bering Sea was one of the central points of the Arctic Report Card and also the subject of an AGU special session entitled “Unprecedented Bering Sea Ice Extent and Impacts to Marine Ecosystems and Western Alaskan Communities“.

We have become increasingly concerned about Bering Sea ice extent in the winter as our deployment of geolocation data loggers has shown that the birds breeding on Cooper Island typically spend over six months of the nonbreeding period utilizing the margins of the pack ice south of the Bering Strait.

Given the anomalous ice conditions in the Bering Sea in the winter of 2017-18, we were very anxious to retrieve the geolocation loggers this past June to see how the birds’ movements and distribution had been disrupted. Preliminary analysis, presented as part of a poster at the AGU meeting, found a dramatic major shift in the guillemots’ distribution for the entire nonbreeding season, with a striking 1000 km (over 600 miles) northward displacement in April, when birds occupied the Chukchi Sea in the Arctic Basin rather than the southern Bering Sea shelf in the Pacific.

Overwinter survival and condition of returning birds was also impacted by the anomalous conditions, with the annual survival of breeders the lowest on record (approximately 70 percent compared to the long-term average of 88 percent) and the first instance of large-scale nonbreeding (pairs occupying a nest but not laying eggs) and eggs being abandoned without being incubated. The number of breeding pairs was the lowest number since the late 1970s and, as we told Seth Borenstein of Associated Press, walking around the colony in 2018 felt like walking through a ghost town.