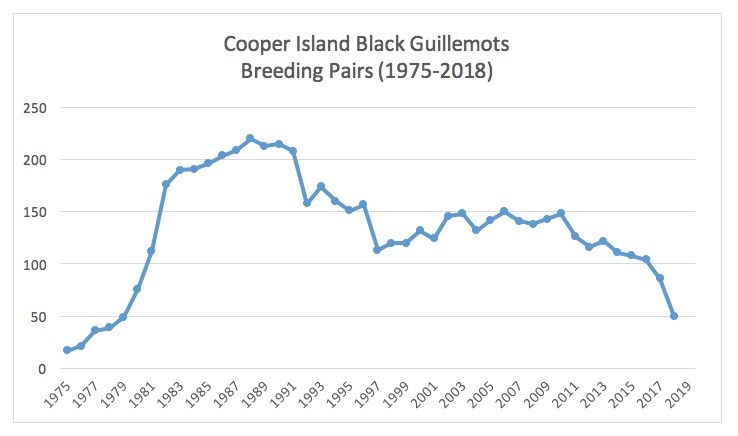

The Cooper Island Black Guillemot colony experiences a major decrease in breeding pairs as long-term decline accelerates.

As of July 6, egg laying ended at the Cooper Island colony and the number of breeding pairs is the lowest it has been in four decades. Only 50 guillemot pairs have laid eggs, down from 85 pairs last year, 100 pairs in 2016 and 200 pairs in the late 1980s.

Cooper Island breeding pairs over the years; it is important to note that the number of available sites has not decreased as the population has decreased, meaning some environmental factor has likely been decreasing the population. Image Credit: Jenny Woodman

A primary reason for the decline was increased overwinter mortality, with almost one third of the last year’s breeders failing to return to the colony. The long-term average for overwinter mortality is ten percent. Also contributing to the decline was a paucity of recruits to occupy the vacancies created by the mortality. Many of this year’s pairs are composed of two birds that lost mates over the winter. All recruitment that did occur were of birds that had fledged from Cooper Island. Immigrants used to constitute the majority of birds recruited into the breeding population.

A potential reason for the high mortality is the lack of sea ice in the area traditionally occupied by Cooper Island guillemots in winter. The unprecedented lack of sea ice over the Bering Sea shelf likely forced birds to occupy the ice edge in the Arctic Basin north of the Bering Strait, where prey resources may not be as abundant.

The 15 geolocators recently removed from returning birds will allow determination of the winter distribution.

The number of breeding pairs also declined due to the number of pairs maintaining nest sites but failing to lay eggs. Nonbreeding by experienced birds and established pairs has been extremely rare on Cooper Island but this year there are 20 such pairs. The presence of such birds, unable to initiate clutches after occupying a nest site, is an indication that overwinter or spring conditions caused both a decrease in the condition of returning birds as well as increased mortality.

Eggs will begin hatching in the third week of July and one has to hope fledging success will be high.