Science writer Jenny Woodman of Proteus writes about Cooper Island research and the current field season.

George Divoky frets–with good reason. In 2016, CNN Correspondent John D. Sutter called him the man who is watching the world melt. The description is as distressing as it is apt.

George sends us regular dispatches from a small field camp on Cooper Island, about 25 miles east of Utqiaġvik, where he has studied a colony of nesting Mandt’s Black Guillemots for the last 44 years. Since his work began in 1975, the research has morphed into one of the longest-running studies of seabirds, sea ice, and climate change.

Guillemots look like small penguins headed off to a fancy party replete with ice sculptures and all-night dancing. Unlike other seabirds that migrate out of the region seasonally, they live out over the frigid waters year-round, only returning to land to breed and fledge their young–this makes them an excellent indicator of how climate change is impacting the Arctic.

Weather delayed the start of this research season in early June. While warm temperatures in the Arctic have made headlines in recent months, unusually late snow and ice kept the guillemots from reaching their nesting boxes until mid-June; the first egg was laid on June 24.

His communications are tinged with an effort to buoy spirits–I’m guessing his own more so than ours. This week, the bad news came first: a 29-year-old female died. He wrote that she had been banded during the first George Bush administration. (While many humans rely on a simple Gregorian calendar, George’s memories appear to be synchronized according to a timeline rooted firmly in geopolitics.)

Bad news was followed with happy; two siblings from the 2014 cohort returned and recruited partners for breeding.

Otherwise, it’s been a stormy week on the island. On July 20, he wrote that the wind was finally dying down. A bad week for the infrastructure, the camp’s weather station was blown over and part of the heavy-duty WeatherPort tarp separated from the frame, which caused a number of things to get wet. On Wednesday he saw record high rainfall for that date.

Egg laying hit an all-time low this year, with fewer breeding pairs than any previous year.

He’s asking questions about how changing ice conditions will impact these seabirds – his seabirds. In his most recent field report, he spoke at length about the relationship between the guillemots and nearshore sea ice. The location of the sea ice impacts how far parents will have to fly to access suitable prey for their chicks. Increased travel time means greater energy expended by parents – for seabirds that live predominantly out in open waters, it’s all about balancing resources and energy. The presence or absence of sea ice combined with the temperature of the ocean waters impacts the availability of Arctic Cod, the small nutritious fish the guillemots prefer.

George hopes the slowly departing nearshore sea ice will keep ideal prey in foraging range for the seabirds. He wrote, the cod is “urgently needed for the colony to reduce its current population decline.”

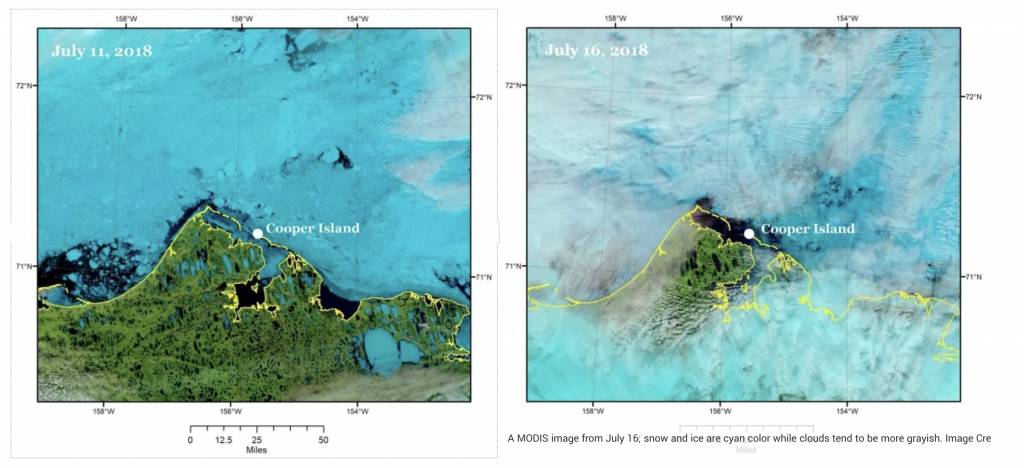

David Douglas is a research wildlife biologist for United States Geological Survey (USGS) Alaska Science Center; he and George are frequent collaborators. This week he emailed the MODIS images displayed above and wrote that Cooper Island was pretty well surrounded until July 16 when the persistent ice immediately around the island broke up and melted.

Studies like George’s will help scientists to better understand the ramifications of long-term warming and less sea ice for wildlife in the region. Impacts to wildlife will directly affect the lives of the people who depend on subsistence fishing and hunting for survival.

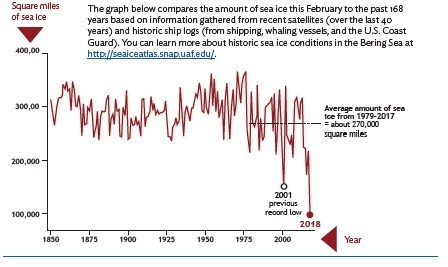

Warming Arctic conditions have persisted with 2018 reaching record lows for sea ice extent, according to a report published by NOAA and University of Alaska Fairbanks’s International Arctic Research Center.

Late ice formation and early retreat in the Chukchi and Bering Seas impacted local communities by making travel for subsistence hunting and fishing dangerous and, at times, impossible. Storm damage and erosion was worsened by exposed shorelines, left unprotected by a lack of sea ice. Island villages and coastal communities experienced flooding and property damage as well. You can read more about the storm impacts here and here.

The report attributes late and minimal ice coverage to warmer temperatures, particularly over the last four years. Increased temperatures combined with stronger storms helped break up weaker ice.

In 2018, there was less sea ice in the Bering Sea than any year since 1850, when commercial whalers began recording this data. Experts agree, loss of sea ice is a result of climate change. Continued warming creates a feedback loop where warming temperatures melt ice; without a reflective snow and ice covering, the ocean absorbs more of the sun’s warming rays and temperatures continue to rise.

As for future winters, what can people expect to see if warming continues at current rates?

“Communities need to prepare for more winters with low sea ice and stormy conditions. Although not every winter will be like this one,” concludes the report, “there will likely be similar winters in the future. Ice formation will likely remain low if warm water temperatures in the Bering Sea continue.”

And for George’s seabirds? How many birds will successfully fledge this year? How many will return next?

We’ll just have to wait and see.