August 11, 2018: Field report

Hatching is finally over with one very late egg hatching today after having been incubated for 34 days; 28 days is normal. The oldest nestling is 16 days old; the chick is gaining weight and doing well like all of the other 45 nestlings.

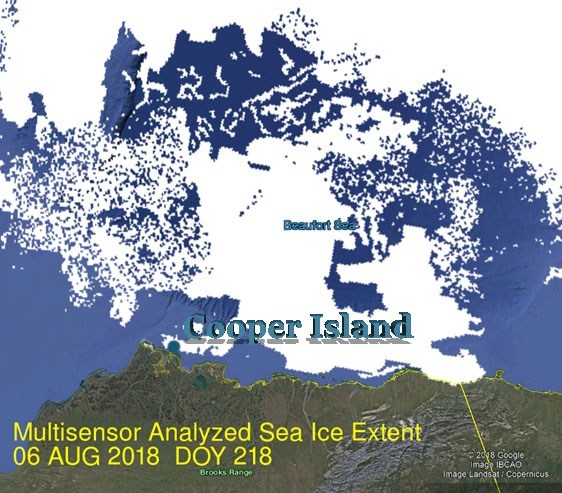

While the main pack ice is well offshore, the Marginal Ice Zone, where ice covers from 18 to 80 percent of the ocean’s surface, extends south to the entire Alaskan Beaufort Sea coast, including Cooper Island. The seascape visible from the north beach now has widely scattered floes, some with rather high vertical relief breaking the horizon, in a nearly flat calm sea. This differs greatly from what was present last year when the first week in August had no ice visible with large swells breaking on north beach. More importantly, last year at this time the sea surface temperature was well above 4 degrees Celsius while this year it is less than 2 degrees Celsius. The guillemot’s preferred prey, Arctic Cod, are typically found in waters from -2 to 4 degrees.

The ice and water temperature conditions are ideal for the parent birds provisioning. Arctic Cod has comprised well over 90 percent of the prey being fed to chicks this year. The two oldest chicks, hatched on July 21, weighed 35 grams at hatching and now weigh 275 grams and 245 grams – the larger of the two experiencing an almost seven-fold weight increase in a 15-day period. A growth rate that rapid requires readily available prey that is both abundant and high energy, as well as two dedicated parents to return to the nest site with a fish every hour. Similar high growth rates are occurring at other nests.

This condition of the nestlings could not be more of a contrast with early August last year. Then, there was widespread mortality of younger siblings as parents could only find enough prey to maintain a single nestling. Arctic cod were absent for much of the nestling period with sculpin and juvenile sand lance comprising most of the prey. Guillemot parents turn to these alternative prey only when Arctic Cod are not available. Sculpin, with their large bony and spiny heads, are hard for nestlings to hold and swallow. They are frequently rejected with numbers building up in nest sites as the young wait for a more preferable fish.

For the moment our daily nest weighing and measuring of guillemot nestlings has been a very positive experience. However, based on what we have seen in the last decade, we know that conditions can change rapidly in August. A strong south wind could move the ice well out of the guillemots’ foraging range or warmer waters could move eastward from the Chukchi and drive away Arctic Cod. We also know that larger and older nestlings are more able to survive changes in prey availability and that the current high growth rates will allow more individuals to survive to fledging.