Even after 44 years, preparing for the field season to study Black Guillemots on Cooper Island is a time of excitement and anticipation as I gather the gear and supplies needed to survive and conduct research for three months on a remote Arctic island. This year the excitement was tempered with a high level of anxiety given last summer’s disastrous breeding season. While the size of the colony has been decreasing since the 1990s, as the guillemots’ sea ice habitat has steadily dwindled, the 2018 breeding season was unique in that 1) the overwinter mortality of breeding birds was three times the long-term average, 2) one third of the returning pairs failed to lay eggs and 3) half of the pairs that did lay eggs abandoned them soon after laying. The result was a colony that in August had only 25 functioning breeding pairs – something hard to observe and process when one has a vivid memory of a 200+ pair colony in the late 1980s.

Back in Seattle I was still processing the data and the implications of the 2018 field season when the U.N. issued a report about the pace of global climate change with a separate report on the Arctic saying a 2-5oC temperature increase was locked in for the region even with major reductions in fossil fuel emissions. While the reports had the positive effect of finally having the media and public focus on the trends in and causes of climate change, along with my findings in 2018 they affected the way I viewed my long-term study. Documenting the pace and magnitude of biological changes in the Arctic seemed all the more important.

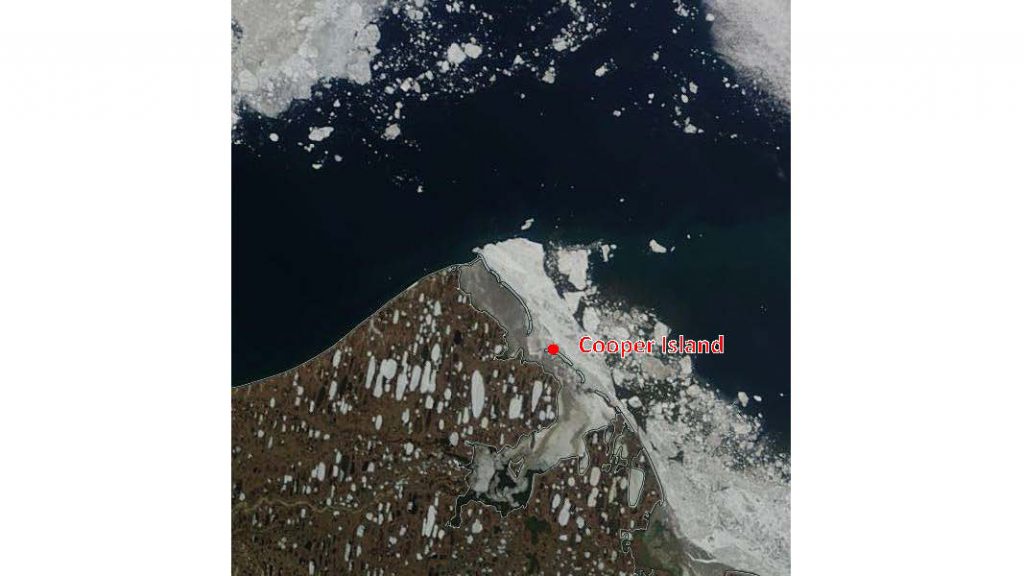

I headed north to Utqiagvik (Barrow) in early June knowing that the guillemots had experienced another year with little sea ice in the traditional wintering area in the Bering Sea and that the Arctic Ocean off northern Alaska adjacent to their breeding colony had unprecedently low sea ice extent for early summer. Conditions like those are bound to pose major difficulties for the Cooper Island Black Guillemots. While I start the season with concern for the long-term trajectory of the colony, I see the 2019 field season as a unique opportunity to document the resilience and adaptability of one of the Arctic’s sea-ice obligate seabirds. I look forward to providing you updates as the breeding season progresses on this website, Proteus, our Twitter feed, and the Friends of Cooper Island Facebook page.