In honor of Earth Day 2020, Joe McNally and Photoshelter will be holding a webinar where Joe will discuss his 2001 and 2019 visits to Cooper Island, the photos and video he obtained during those visits and the importance of conservation photography in engaging and educating the public. We had planned to have Joe attend our annual Seattle update at Town Hall Seattle, which had to be cancelled due to the need for social distancing and are glad he is able to discuss his Cooper Island work in this webinar. You can register for the webinar at this link or view the full recording early next week at the Photoshelter website. The video Joe will be discussing can be viewed on YouTube at this link.

My long-term relationship with Alaskan seabirds began the same year as Earth Day. In April 1970, during my first year of graduate school, I attended events celebrating the first Earth Day and was full of optimism as society demonstrated a heightened environmental awareness. Later that year I made my first trip to Arctic Alaska, where, I conducted seabird observations from a Coast Guard icebreaker, censusing seabirds in waters offshore from the rapidly developing Prudhoe Bay oil field.

I, of course, had no idea that my internship at the Smithsonian Institution in the summer of 1970 would lead to me spending the next half century in Arctic Alaska. Nor could I ever have imagined 45 of those years would be spent on a remote island studying the life history of an ice-associated seabird, Mandt’s Black Guillemot. My review of seabird literature as part of my graduate studies, had made me extremely interested in the diverse ways seabird species have adapted to raising their young on land while being dependent on marine food sources. The colony of guillemots I discovered on Cooper Island in 1972 provided an ideal situation in which to study that phenomenon.

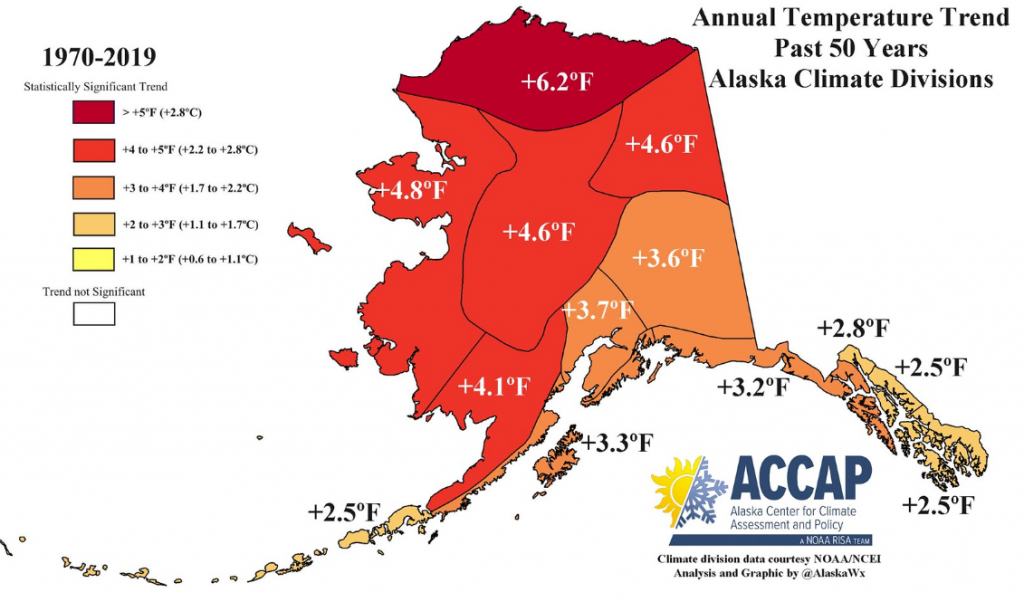

It would have been impossible to know – and would have been inconceivable at the time – that the region of the Arctic where I would be conducting a multi-decadal study, would be one of the most rapidly warming areas of the world in the next half century. Nor could I ever have known how the resulting changes in sea ice would affect my study species. A thriving colony of over 200 breeding pairs in the 1980s, most successfully raising young, would be reduced to less than 80 pairs by 2019, with most pairs unsuccessful due to the absence of the previously abundant ice-associated prey.

While we are currently focused on the corona virus and its impact on health and economic security, it is important to remember that the warming of our planet continues with NASA projecting that this could be the warmest year on record. The ongoing study on Cooper Island remains one of the few biological metrics of the impact of sea ice loss on marine ecosystems in the Arctic and it is important to maintain it as the Arctic continues to change. The melting of sea ice is continuing with the Arctic predicted to be free of ice in summer before mid-century, although models show a decrease in carbon emissions will reduce the frequency of ice-free summers. Optimistically our continued research will document the resilience of a species in response to unprecedented changes in its environment, allowing the Cooper Island colony to persist in an ice-free Arctic. Pessimistically, we could be recording the last days of the canary in the coal mine.

If there is a bright side to Earth Day 2020, with most of the world under lock down, it is that humans are being shown the consequences of not taking action on pressing societal issues – and may be able to address the issues that have warmed the plant over the last half century.