The two weeks before I head north to Cooper Island are always an interesting mix of anticipation of the upcoming three-month field season combined with regret at having to leave my family and friends in Seattle. In recent years, as the Arctic continues to warm, there is a good amount of uncertainty as to what the next field season might bring. While the Nanuk cases now protect the Black Guillemots eggs and nestlings from polar bears forced to Cooper Island because of the melting sea ice, the increasingly frequent decreases in prey availability as the pack ice recedes and seawater warms are causing large numbers of chicks to starve in the nests in August.

Recently the 2015 field season took on an additional element of concern as Shell Oil was approved to drill for oil off the Alaskan Arctic coast this summer. One of the rigs Shell will be using, the Polar Pioneer, is currently six miles west of my house in Seattle. For much of this summer, if all goes as Shell plans, it will be 175 miles west of my cabin on Cooper Island.

As the kayakers who protested the arrival of the rig in Seattle this past weekend made clear, the decision to allow Shell to drill in the Chukchi Sea has the potential of harming the Arctic both directly and indirectly. Direct harm would come from an oil spill – and according to the BOEM (Bureau of Ocean Energy Management), which approved Shell’s plans, there is a 75% chance of one or more large spills should oil production occur in the lease area. There is also a risk of a spill from exploratory wells, as the Deepwater Horizon showed, and Shell is proposing to drill six exploratory wells this summer. The indirect harm would occur if and when the oil is transported to places where it can be used as a fossil fuel and help to increase the level of atmospheric CO2, which is already at a record high of >400 ppm and has contributed to Barrow, Alaska (25 miles west of Cooper Island) now having an annual temperature that is 5°F warmer than in the late 1970s. The melting of snow and sea ice caused by that warming was the primary way the Cooper Island guillemots were being impacted by fossil fuels over the last 40 years. But it is now clear that the drilling by Shell in the Chukchi Sea could pose a major direct threat to the population.

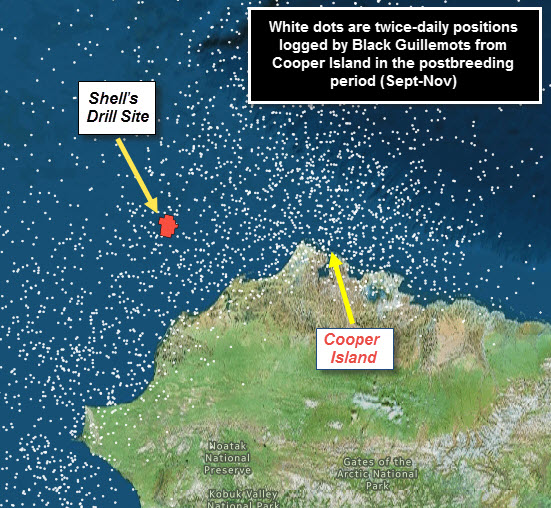

The magnitude of that threat became more apparent to me this past week as I completed the processing of data files showing the distribution of Cooper Island guillemots in the three months after they leave the island. By outfitting a small number of guillemots with geolocators at the end of the 2011-2013 breeding seasons and retrieving the units the following year, we can now see where the birds have spent the intervening nine months, as the light-sensitive geolocators record daily sunrise and sunset times that identify a bird’s noon and midnight position within an approximately 30-mile radius.

The map I generated for the eastern Chukchi Sea and Western Beaufort Sea surprised me for two reasons. The first was how widely dispersed the birds are after breeding. The second was how common they are in proximity to this summer’s drilling location – and in the entire Lease Sale Area 193. It is important to remember that the above map shows the positions from only 10 birds (on average) monitored each year. Two hundred guillemots now breed on the island annually, with an additional 50-100 young fledging every year, so the frequency of Cooper Island birds in the drilling area is even higher than shown on the attached map. It appears that in the fall the majority of the population occupies the area where drilling has been proposed. The annual replacement of flight feathers occurs during the fall, rendering the the guillemots flightless for a period of time, making them extremely vulnerable to a spill.

I hope to be out on Cooper Island the first week in June and Shell says its drilling season could begin in early July. I will be blogging from the field – including posts on Facebook (Friends of Cooper Island) and Twitter (@CooperIslandAK) – that will allow anyone interested to find out what is happening on the island with the guillemots, polar bears and me. My summer will include both retrieving and deploying geolocators, which I now realize are an important part of assessing the potential threats to the Cooper Island Black Guillemots.