The Arctic is warming twice as fast as the rest of the world. For the past 42 years I have had a front row seat on Cooper Island off northern Alaska studying the Black Guillemot, a high Arctic seabird that is responding to the earlier snow melt and diminishing summer sea ice cover. Early melting of snow had allowed the birds to breed as much as two weeks earlier than they did in the 1970s, which facilitated a major increase in the size of the colony in the 1980s. But increasing warmth after 1990 has decreased breeding success by reducing the extent of summer sea ice near the island and so the availability of Arctic cod, the preferred prey of guillemots.

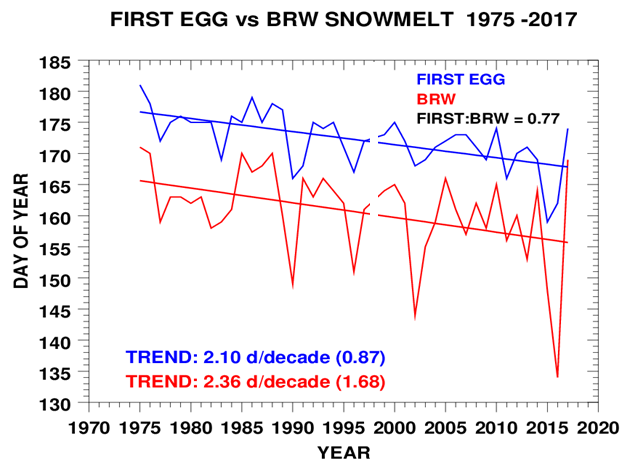

Egg laying was so early in 2015 and 2016, with first eggs in the colony on 8 and 10 June respectively – see last year’s post The Earliest Year – that I arrived on the island those years just as the first eggs were being laid. Having recorded the first egg in the colony since 1975, I didn’t want to arrive late this year so, based on date of breeding initiation in the past two years, I flew to Barrow (Utqiagvik) on the first of June, thinking I would go out to Cooper Island a day or two later. However, unlike the past two years, snowmelt in Barrow was not early —it was extremely late. Snow at the NOAA station just outside Barrow was the latest since 1988, with snow disappearing on June 18th – compared to 2016 when melt occurred on May 15th. For data and discussion of these years, see Drivers and environmental responses to the changing annual snow cycle of northern Alaska

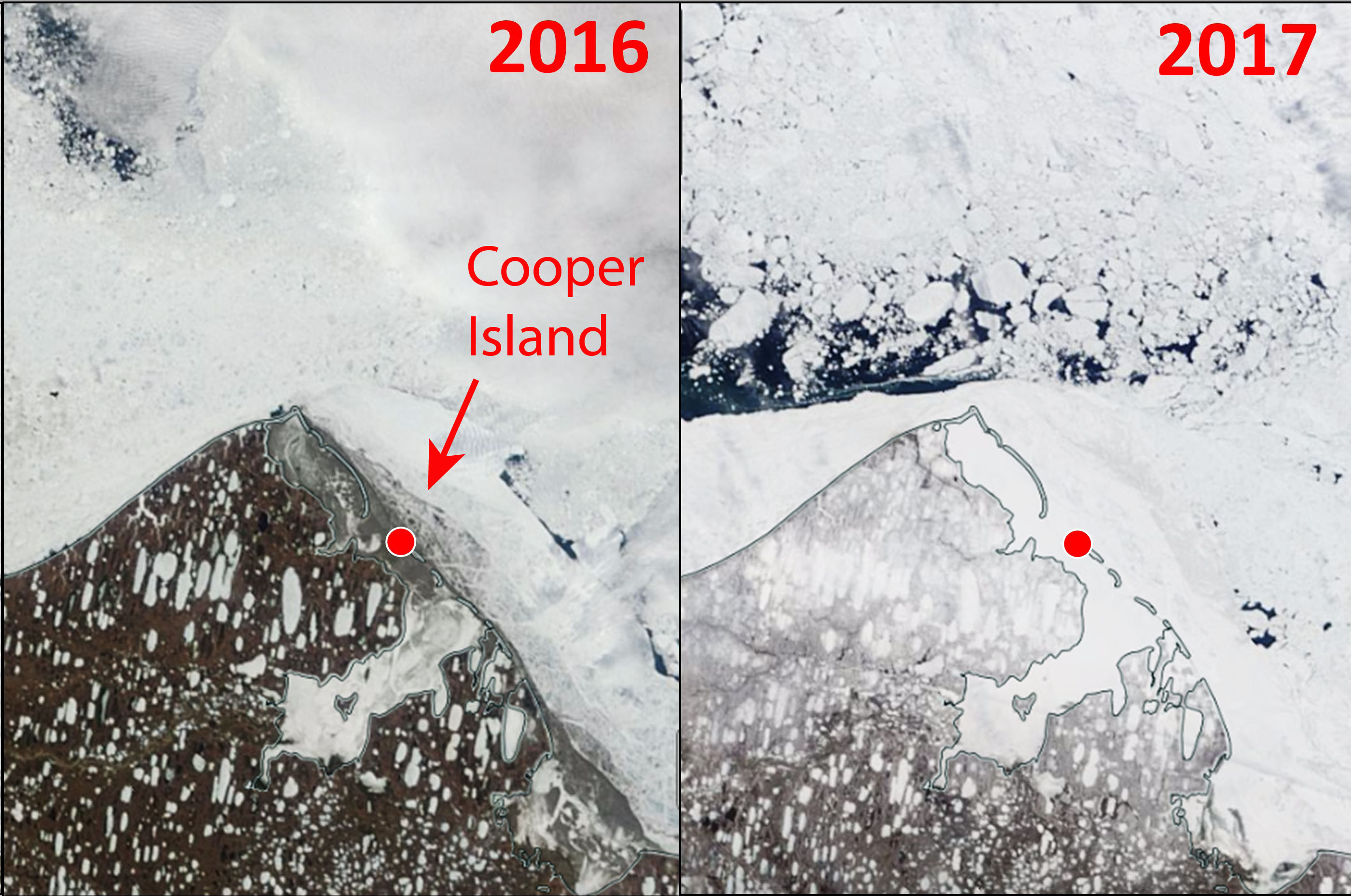

Satellite images of northernmost Alaska on June 11, 2016, and June 11, 2017. MODIS images obtained from NASA Worldview

Knowing that the guillemots’ arrival on the island, as well as egg laying, is dependent on snowmelt, I waited until June 14th to fly out to the colony. As we circled the island before landing I saw it was surrounded by sea ice as far as the eye could see. There were snowdrifts over half of the island, including a major drift surrounding my cabin. Over the winter I had filled the cabin, as usual, with most of field gear I need to survive on the island for the three summer months of the field season, and unpacking occupies my first 2-3 days in the field. This year all items had to be taken not just out of the cabin but to the edge of the snowdrift. The upside of such a large snowdrift is that it will supply water for the camp for much of the summer when put into plastic containers to melt.

The snow drift around the cabin on Cooper Island

Snowmelt on the island proceeded slowly in June and the first guillemot egg in the colony was laid on June 23rd, almost two weeks later than the past two years and maintaining the high correlation between Barrow snowmelt and guillemot breeding phenology.

Trends and correlation between Barrow snowmelt and guillemot breeding phenology.

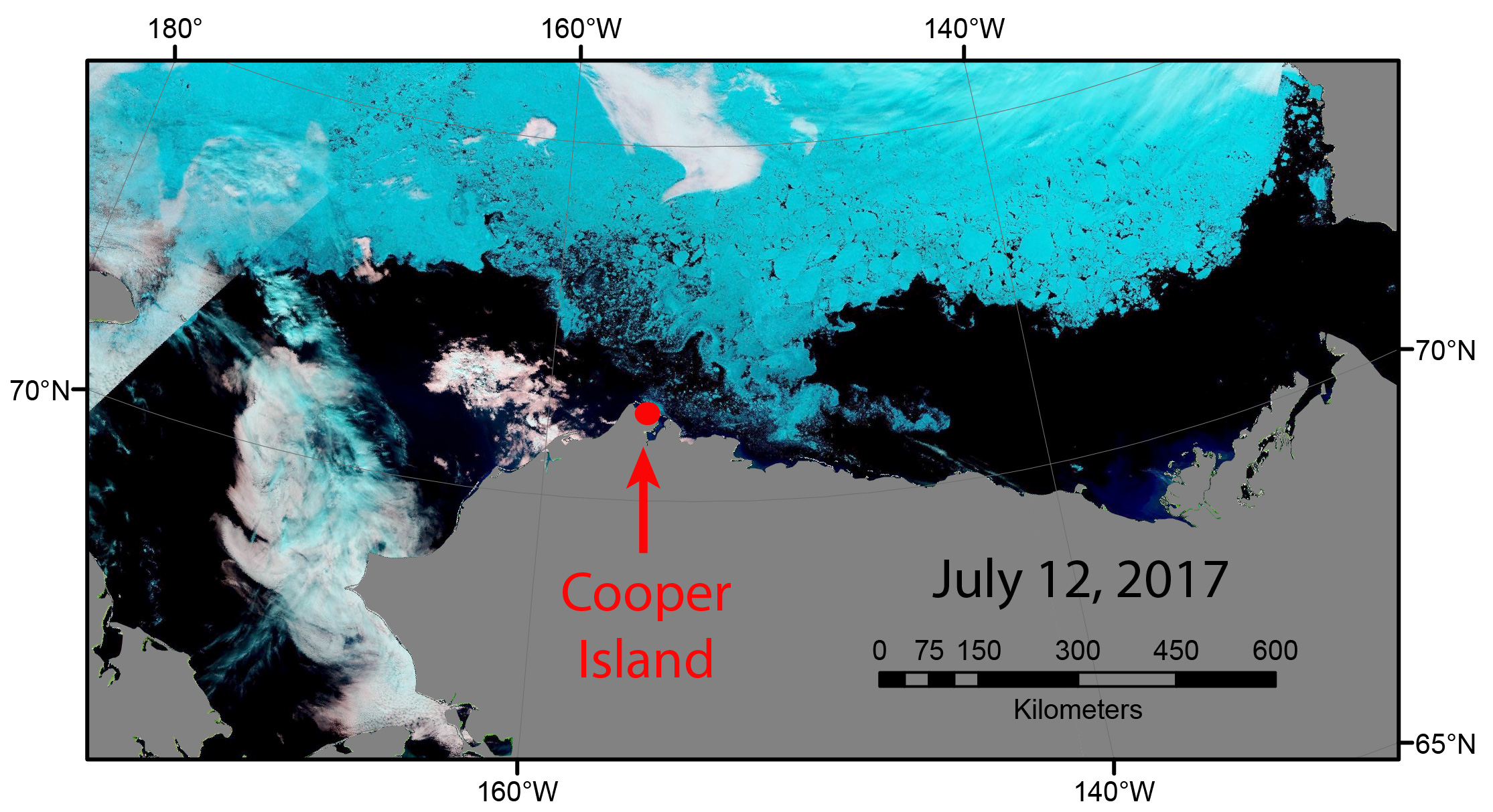

In contrast to this abundance of late snow on the island in June, sea ice off northern Alaska (and throughout most of the Arctic) was at record lows for the month . The large mass of shorefast ice that surrounded Cooper Island last month is currently breaking up and once gone, the distance from the island to sea ice will be large and will increase as the ice continues to melt and retreat in July and August.

The combination of late snowmelt and early sea ice melt could have major effects on this year’s breeding success. Parent guillemots will be feeding nestlings later than in recent years, late July to early September, and Arctic cod, the preferred prey of the guillemots, will be unavailable should sea ice reduction proceed as expected. Currently, Arctic sea reduction is on a trajectory to match the record low September extent of 2012: Arctic Sea Ice Extent .

July 12, 2017, MODIS satellite image of the Chukchi and Beaufort Seas. This false-color composite is shown to help distinguish clouds (more white) from sea ice (more blue). Open ocean is black.

The disparity between this year’s extremely late snow melt and early sea ice melt and retreat has been a surprise and a clear example of the breadth of atmospheric and oceanographic factors that affect the environment of guillemots. Egg laying in the colony has just ended and parent birds are now incubating their eggs, which they do for 28 days. When young start hatching in late July, guillemot parents will likely be foraging for fish in near-ice-free waters. Their ability to find suitable and sufficient prey to successfully raise their young will provide insights into how the species will adapt and how the colony will maintain itself as summer sea ice continues to decrease in future years.