The standard and far-too-simplistic “test” of whether someone is an optimist or a pessimist is to ask if they consider half a glass of water to be half full or half empty. The major flaw in the test is that it implies a steady state situation. If the glass is being filled with water, one has reason to be optimistic about half a glass. If it is being drained, there is reason for pessimism. The increasing or decreasing trend of a resource needs to be considered in deciding whether to be optimistic or pessimistic about the currently observed conditions.

This summer the Black Guillemot colony on Cooper Island had 100 breeding pairs. Guillemots do not breed in the thousands or tens of thousands, as do many seabirds, and a 100-pair colony is a rather large aggregation of these beautiful birds. Anyone familiar with breeding guillemots who happened to visit Cooper Island this summer would likely be impressed with the 200 individuals breeding here.

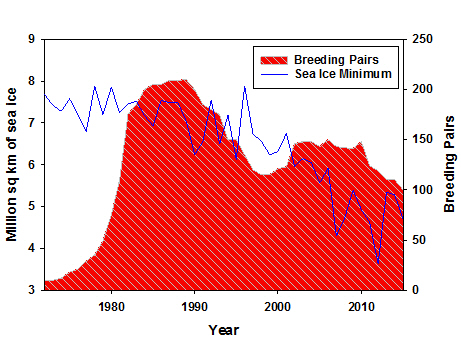

However, it would be hard for anyone familiar with the history of the Cooper colony to be optimistic about its future. Starting in 1975, we modified wooden boxes, floorboards and other debris on the island to create 200 nest cavities by the early 1980s. Guillemots quickly occupied the nest sites and the breeding population increased from 18 pairs in 1975 to just over 200 pairs in 1989 (graph below) when all potential nest cavities in the Cooper colony were occupied by breeding pairs.

This year, 2016, there are still 200 nest cavities. The guillemots now nest in polar bear-proof Nanuk plastic cases that replaced each of the more vulnerable wooden sites in 2011. The birds took to the new cases immediately, parent birds and nestlings clearly feel more secure in them and loss of nestlings to polar bears is now near zero – but this year half of the available nest cases are empty and no guillemots are breeding there.

We are currently examining the specific reasons for the colony’s decline to half of what it was in 1989 in collaboration with avian demographers but it is appears to be due to the guillemot subspecies on Cooper Island being one the few ice-obligate seabirds in the Arctic. In a rapidly warming world the Arctic is the region that is warming most rapidly with dramatic and clearly visible effect on the region’s snow and ice habitats. The decline in the Cooper Island colony started in 1990, the same year that warming temperatures in the region allowed the island’s guillemots to begin laying eggs earlier (as discussed in a previous post [link to last post]) and the decreasing trend in annual summer sea ice extent began. Decreased summer sea ice has reduced the availability of the guillemots’ preferred prey, arctic cod, resulting in lower breeding success on Cooper Island and likely other colonies and, in this century, has increased polar bear presence on the island – which until we provided nest cases greatly reduced breeding success.

Given the loss of Arctic sea ice, it is not surprising that the Black Guillemots have also declined. When the Cooper Island colony was near 200 pairs in the late 1980s, the annual minimum extent of sea ice in September averaged over 7 million square kilometers. As the guillemot population was declining in the last decade to its current 100 pairs, September sea ice extent has dropped as low as 3.6 million square kilometers – nearly half what it was when the Cooper Island study began. In short, both Arctic summer sea ice and the Cooper Island guillemot colony have been reduced by half in the last quarter century.

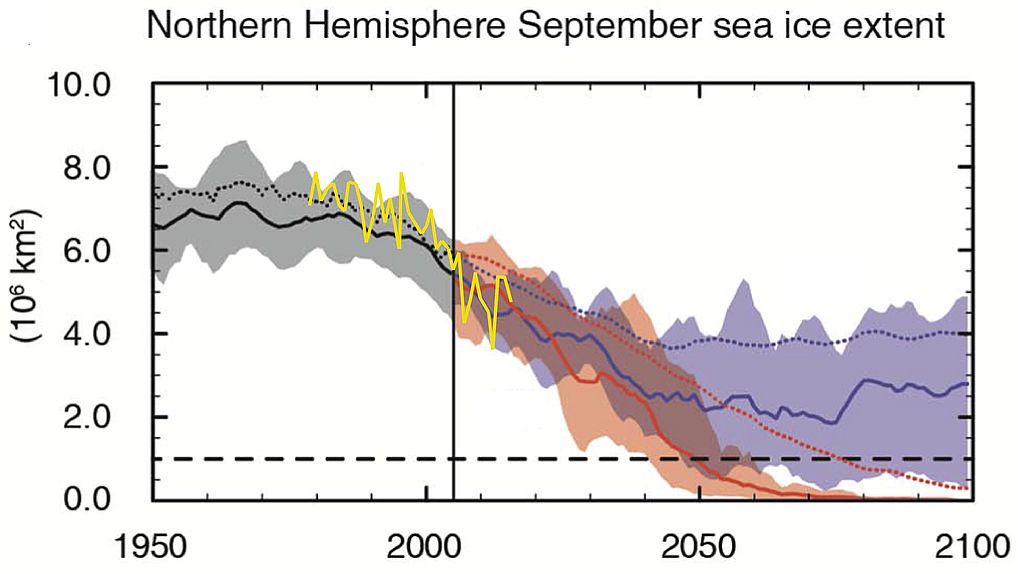

The future trajectory of summer sea ice seems clear. Continued carbon emissions will cause continued warming, which will cause continued ice loss. All climate models project continued decline and eventual disappearance of Arctic sea ice if carbon emissions are not greatly reduced (graph below). The path of the Cooper Island guillemot population, however, is less certain. Like all animal populations the birds currently breeding on Cooper Island may possess sufficient behavioral plasticity to adapt and evolve to accommodate new conditions, just as their ancestors may have possessed when they adapted to exploit ice-covered waters. Some guillemots may be able to survive and even prosper in an Arctic without summer sea ice – which, unlike the animals that have come to depend on it (including not only the Cooper guillemots but arctic cod, walruses, seals, and polar bears), cannot adapt and somehow stay frozen at temperatures above freezing.

Observations of Northern Hemisphere minimum September sea ice extent (yellow line), and time series of global climate model projections (5 year running mean) and uncertainty (shading) for scenarios RCP2.6 (blue) and RCP8.5 (red). Black (grey shading) is the modelled historical simulation using historical reconstructed forcings. The RCP8.5 emissions scenario depicts a future where current rates of emissions continue unabated throughout the century, and the RCP2.6 scenario depicts a future in which the aims of the Paris Agreement are fulfilled.

Figure was adapted from the IPCC Summary for Policy Makers, 2013, Figure SPM.7b (http://www.climatechange2013.

My days on Cooper Island in August are consumed with weighing nestlings. Regular contact with the young of any species is bound to make one feel optimistic – it is still a wonder to me how quickly chicks grow from little balls of fluffy black down into gawky “teenagers” preparing to fledge into the Arctic Ocean, unaccompanied by their parents. But as I walk through the colony seeing only open ocean to the horizon – where in decades past I saw large expanses of sea ice – I have to wonder how many young will survive to breed, and what conditions they may encounter should they return to Cooper to nest at sites we have been monitoring during the recent decades of rapid warming and plan to monitor in the even warmer future.

Early August has brought the first pulse of polar bears to Cooper Island, stranded here as their sea ice habitat that provides them a platform to walk on and hunt seals from is rapidly disappearing to the north. The bears, some of whom sleep for days on the island after swimming an unknown distance from melting sea ice, remind me that an entire biological community is being impacted by this halving, and eventual disappearance, of summer sea ice. However optimistic I may feel about Black Guillemots’ ability to adapt to ice loss, I am aware I am observing the loss of one of the world’s most unique ecosystems.