George’s latest field report describes his daily nest checks as parents are feeding chicks to prepare them for fledging.

Black Guillemots have their young remain in the nest for almost five weeks, being nearly adult weight and independent of the parents when fledging. Returning to the nest with a single fish in their bill is a breeding strategy found in all member of the genus Cepphus; it reflects the abundance and predictability of prey in the nearshore waters where parents forage while provisioning young.

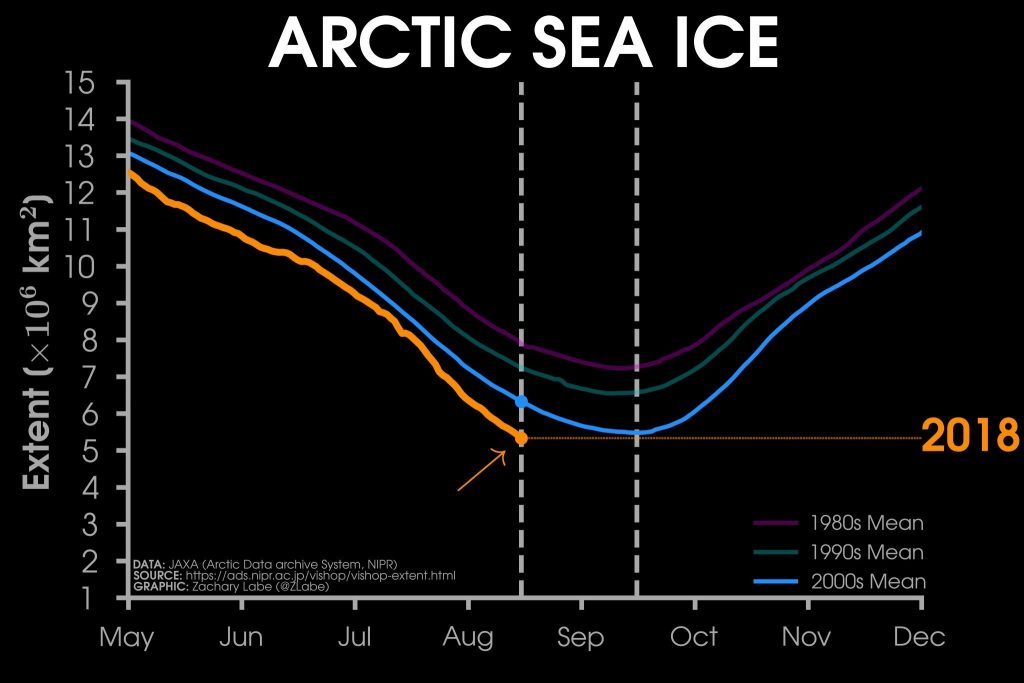

For guillemots breeding in subarctic and temperate areas, where the nearshore provides a diverse and ample supply of forage fish, the strategy works well. In the Arctic, however, Mandt’s Black Guillemot has had to adapt to a different nearshore environment. Because of sea ice covering and scouring the nearshore much of the year, and the low productivity and biodiversity of the region’s marine waters, there is a typically a paucity of nearshore fish to feed their young.

The sea ice is central to supporting an ecosystem, with Arctic Cod being the primary forage fish, that can provide an abundant source of prey when the edge of the pack ice occupies the nearshore. Mandt’s Black Guillemot has been able to breed in the Arctic “nearshore” due to this presence of sea ice near their breeding colonies.

The strategy worked well as long the breeding colonies were adjacent to the Arctic pack ice and sea surface temperatures were low. These conditions were present for the first thirty years of the Cooper Island study and the growth and fledging rate of guillemot nestlings was high. Now, as summer sea ice retreats earlier and farther from the coast, nestlings and their parents could no longer count on having 35 days of high prey availability. This has resulted in decreased chick growth, increased mortality, and poor condition of those nestlings surviving to fledging.

This year, with ice visible north of the island until a few days ago, there was an abundance of Arctic Cod. A walk through the colony found many parents flying back to their nests with adult cod (some bigger than six inches). Chick weights and survival reflected this abundance with no mortality of nestlings yet being recorded this year.

However, since sea ice was blown offshore by strong south winds two days ago, most chicks have been losing weight with others having little or no growth. Based on what we have seen in past years, parent birds should soon be shifting their prey choice to the more predictable – but less preferred – sculpin. The abundance of sculpin – which are present in a range of water temperatures – and the parents’ ability to shift their foraging strategies will determine the fledging success of the nestlings this year.

One of the reasons nesting guillemots are such good monitors of prey availability in nearshore waters is the lengthy time parent birds have to provision their nestlings, as guillemot young stay in the nest for five weeks after hatching. During that time parent birds are foraging for most of each day and returning to the nest nearly once an hour with a fish.

The current conditions of diminished sea ice have us approaching our daily nest checks with far more uncertainty than we did in the first decades of our study – when we expected chicks to have a steady growth rate until fledging. In the next few weeks a nest case could contain nestlings in poor condition, signs of hunger-motivated sibling aggression on the younger chick, or a number of large sculpin uneaten by the nestlings due to the size of their spiny bony head.

The one bright spot in our nest checks this year has been site E-11 where the chicks hatched from the first eggs laid this June. These nestlings are extremely healthy having been raised on adult Arctic Cod by two highly experienced parents, both over 20 years of age. The oldest nestling is just two to three days from fledging and demonstrates the benefits of parents laying eggs as soon as spring snowmelt allows.