During the 1970s, in my first years in Arctic Alaska, people would talk about it being a “late year” or “early year” when discussing the timing of snowmelt, arrival of birds, flowering of plants, or the melting of sea ice. It was generally assumed one would rarely or ever see an “average year” but that over time annual variation would produce approximately equal numbers of late and early years with no reason to believe there would be any long-term trend to earlier or later years during the course of one’s lifetime.

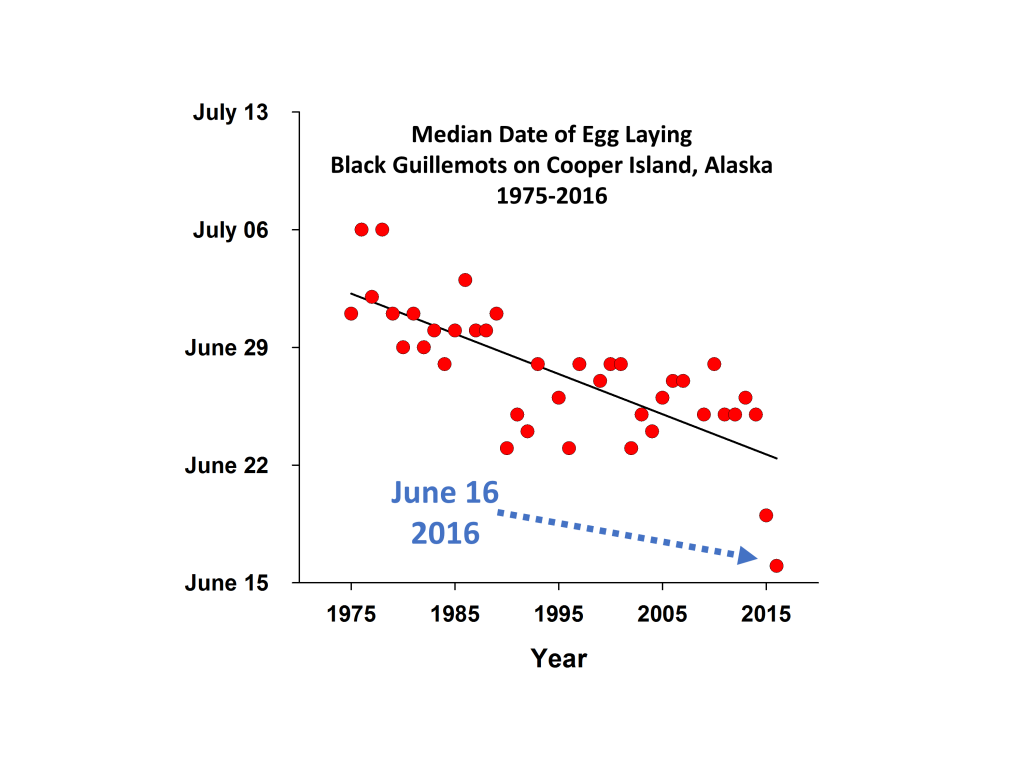

That proved to be true for the first fifteen years monitoring the timing of breeding of Cooper Island’s Black Guillemot colony. One of the best ways of measuring the timing of breeding in a seabird colony is to obtain the median date of egg laying – the date when half of the breeding females in the colony have started to lay eggs.

From 1975 to 1989 the median egg was laid in late June or early July. However, in 1990 the consistency of the previous 15 years was broken as egg laying occurred approximately one week earlier than in previous years. The start of the breeding season for the Black Guillemots on Cooper Island is related to the timing of snow melt because winter snow blocks the entrances to the ground level nest cavities and females need access to a nest before they will begin to form eggs. The shift in timing of breeding beginning in 1990 reflected a change in regional atmospheric circulation (the Arctic Oscillation) that resulted in warmer spring temperatures, earlier snow melt and earlier egg laying.

While the early breeding in 1990 was a major surprise at the time, what was almost more surprising was that the it was followed by a quarter century with no trend in the timing of egg laying at all – just an approximately equal numbers of early and late years, centered around a new average.

It is the two periods of relative stability (1975-1989 and 1990-2014) in the guillemot’s timing of breeding that make the findings on Cooper Island in 2015 and 2016 all the more intriguing. Last year’s 2015 field season saw the median date of egg laying occur on June 19, three days earlier than the previous early record and 6 days earlier than the 1990-2014 average. The early 2015 season followed record warm spring temperatures recorded at NOAA’s Observatory 20 miles away in Barrow.

This year things were again warm in Barrow with snowmelt at NOAA’s observatory the earliest on record and I assumed it would again be an early year on Cooper Island. But I was surprised at just how early it has been, with the median date of egg laying occurring on June 16, three days earlier than last year and more than two weeks earlier than the timing of egg laying when the study started in the late 1970s.

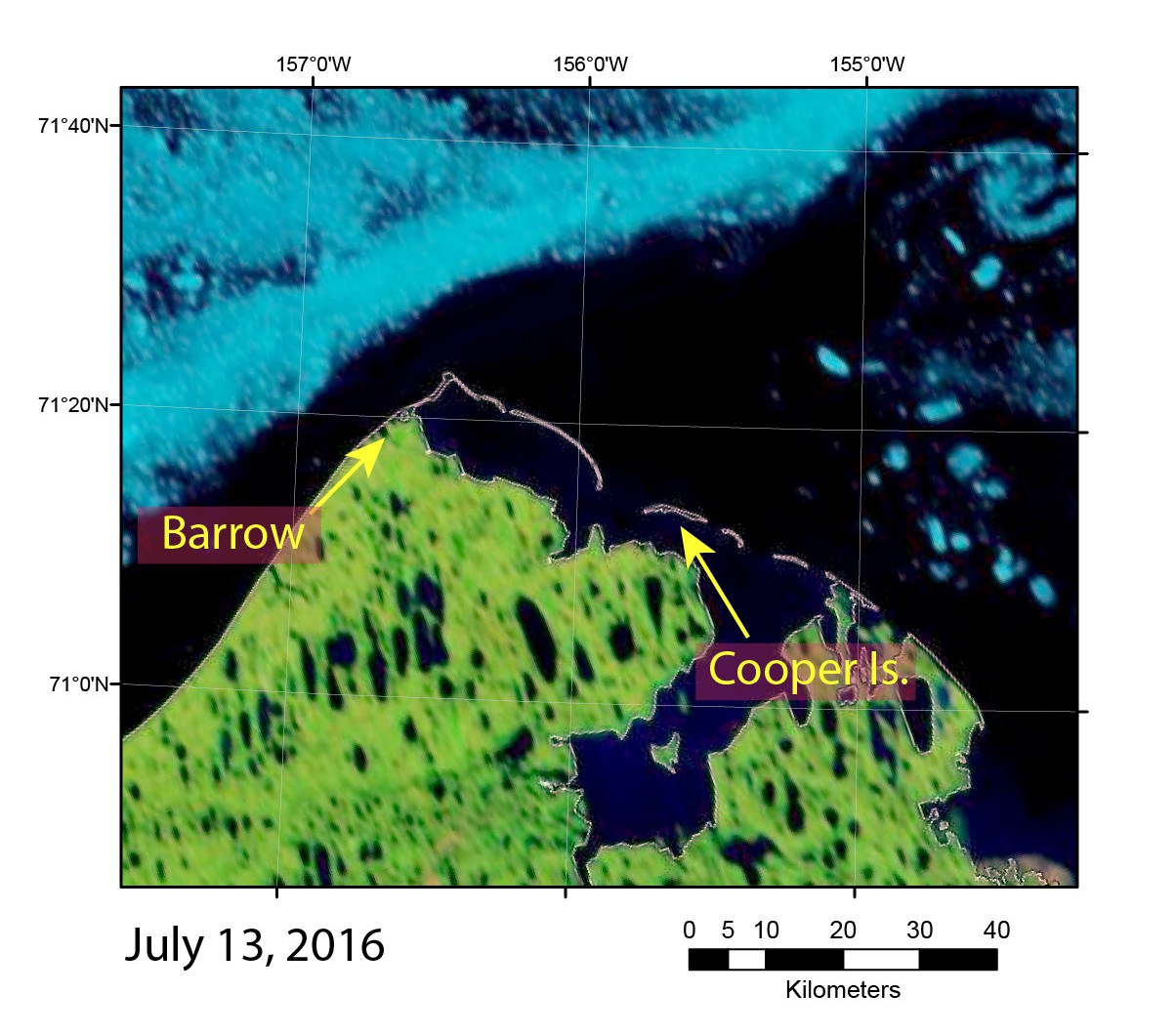

Early egg laying is typically considered a good thing for Arctic birds, as it provides more time for raising young before fall migration. For the Black Guillemots, however, the warmth that has been melting snow and allowing earlier breeding has also been melting the sea ice in the adjacent Arctic Ocean. Black Guillemots in the Arctic are adapted to feeding in the cold waters around the sea ice where they can find their preferred prey, Arctic Cod. For the last 15 years, loss of sea ice in late July and August, when parents are feeding their young on Cooper Island, has caused a lack of food resulting in lower fledging weights, higher nestling mortality, and overall decreased nesting success. Black Guillemot chicks are just beginning to hatch now (mid-July) and will remain in the nest for the next five to six weeks. The ice-associated prey available to their parents may be again limited this year as the sea ice melt has been on a near record pace and a recent satellite image shows most of the waters used by Cooper Island’s guillemots are already free of ice.

All species and ecosystem processes in the Arctic have annual cycles tied to the timing of spring snow melt, which is trending earlier due to climate warming. The 42-year data set on the timing of Black Guillemot breeding on Cooper Island provides unique insights into the biological consequences of the well-documented physical changes occurring in the Arctic. Unfortunately there are very few multi-decadal data sets documenting the changes that have occurred to Arctic species, and that paucity of data makes the study on Cooper Island’s Black Guillemots all the more important to preserve and continue.

The Cooper Island study is maintained by donations to our nonprofit, Friends of Cooper Island, a 501(c)3. Your donation will help us continue to monitor a warming Arctic.