Please join us at Town Hall Seattle on the evening of Tuesday, April 23. The five-decades of research of a seabird colony...

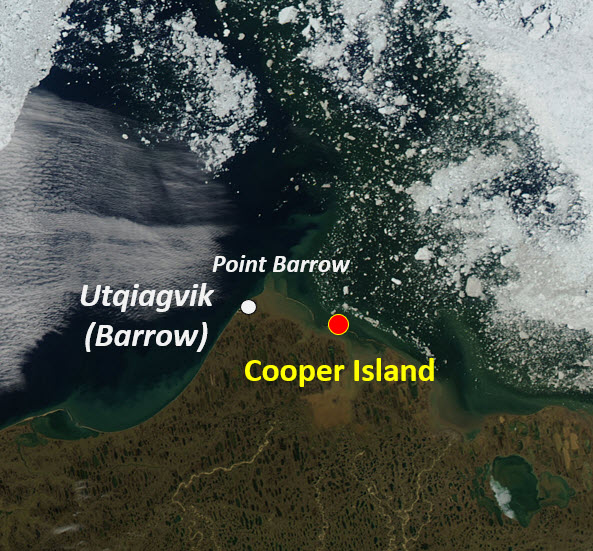

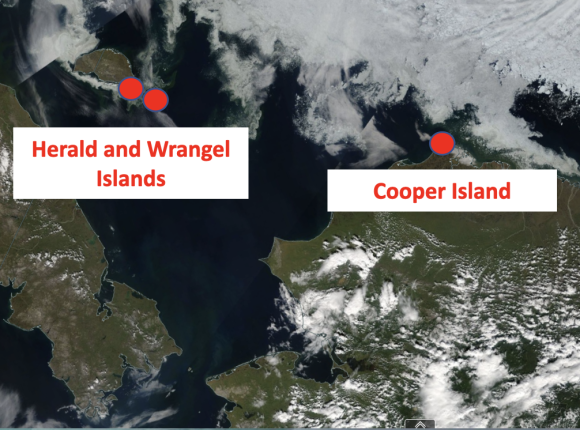

Latest from Cooper Island

Black Guillemot Breeding Pairs

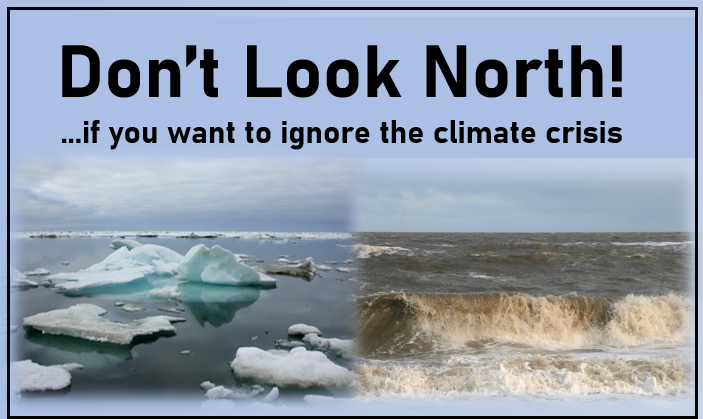

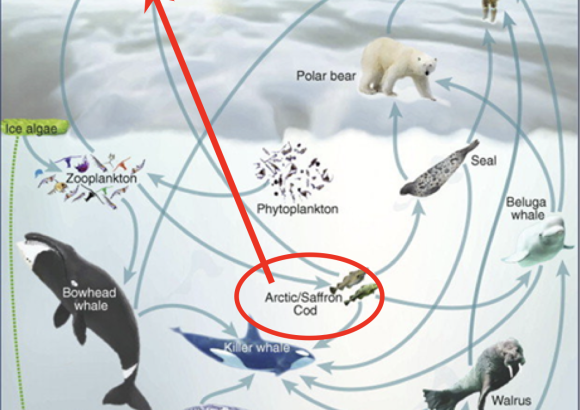

With the ice packs receding further from breeding grounds…

Black Guillemots can’t find enough nutrient-rich fish to feed their young.

Fifty Summers in the Arctic

Stories of Change, Science & Hope

This is the 2022 Cooper Island Annual Update from March 7, 2023 at Town Hall, Seattle. In addition to providing an update on the status of George’s seabird study colony and the melting Arctic, George shares stories (some funny, some sad) about the joy and heartbreak of maintaining a remote field camp for five decades.

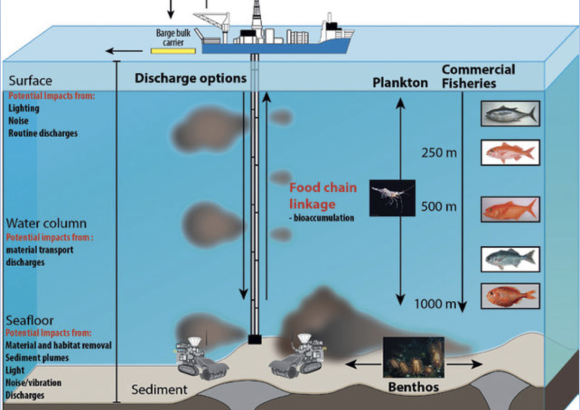

Arctic Sea Ice Concentration

Sea ice concentration = ratio of sea ice to water

<30% sea ice concentration = ships can travel here.

>90% = solid ice.

Arctic Cod is a high protein food source that Black Guillemots feed their chicks. Arctic cod only live under sea ice packs.